Disenrollment is not indigenous to Native America. It is a creature of the United States. The origins of tribal "disenrollment" are traced to the United States’ paternalistic assimilation policies of the 1930s. (Federal Indian rolls and removal therefrom date back even further--to the early 1800s.)

In 1934 the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (“IRA”), wherein the federal government took an extremely active role in framing tribal membership rules. The IRA contained a definition of who would be recognized as an indigenous person by the federal government: The individual must be a descendant of a member residing on any reservation as of June 1, 1934, or a person “of one-half or more Indian Blood.” 25 U.S.C. § 476.

The United States’ intent was to limit membership “to persons who reasonably can be expected to participate in tribal relations and affairs.” Office of Indian Affairs, U.S. Dep't of the Interior, Circular No. 3123 (1935), reprinted in 2 Am. Indian Policy Review Comm'n, 94th Cong., Task Force No. 9 Final Report app. at 334 (Comm. Print 1977). The IRA also urged tribes to adopt a constitution and included a boilerplate that tribes were encouraged to adopt. And because tribal constitutions were subject to federal approval, the IRA definition of “Indian,” including its blood quantum requirement or some variation thereof, as well as concepts of "disenrollment," found their way into most tribal constitutions, even those that did not adopt the boilerplate IRA constitution.

In fact, even those tribes that opted to forego adopting a constitution were often persuaded to adopt these concepts somewhere in their organic law as a “consequence of the [federal government]’s control over federal services and tribal monies.” Suzianne D. Painter-Thorne, If You Build It, They Will Come: Preserving Tribal Sovereignty in the Face of Indian Casinos and the New Premium on Tribal Membership, 14 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 311, 341 (2010).

Thus, “while it is true that membership in an Indian tribe [wa]s for the tribe to decide, that principle is dependent on and subordinate to the more basic principle that membership in an Indian tribe is a bilateral, political relationship” under which the United States had set the terms. Margo S. Brownell, Who is an Indian? Searching for an Answer to the Question at the Core of Federal Indian Law, 34 U. Mich. J.L. Reform 275, 307 (2001). The Indian Self-Determination Education Assistance Act of 1975, additionally required that tribal governments devise formal membership regulations, in order for the tribe to receive certain federal self-determination funding. The United States suggested such regulations, which like its boilerplate IRA constitutions, included notions of blood quantum and disenrollment.

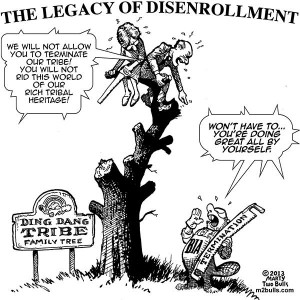

In all, for the last 80 years, the United States has set the terms of tribal membership, i.e., "Indian," "blood quantum," "membership," "base rolls," and of course "disenrollment." And for good measure, tribal acceptance and implementation of those unconscionable terms have been conditions precedent to self-determination funding since the 1970s.

Despite having invented disenrollment and foisted it upon tribal governments, the United States now suggests that it has no "business trampling on tribal sovereignty and self-governance" by interceding in tribal disenrollment disputes. Or, as Nooksack Councilwoman Michelle Roberts -- a member of a the Nooksack 306 -- put it to Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin Washburn: "It is Frankenstein in Indian country that the United States has created, and now ignores."

Galanda Broadman is an American Indian owned firm dedicated to advancing tribal legal rights and Indian business interests. The firm represents tribal governments, businesses and members in critical litigation, business and regulatory matters, especially in the areas of Indian Treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, taxation, commerce, personal injury, and human/civil rights.