Do you have a county birth certificate for your great grandmother from the late 1800s?

Were your ancestors listed on federal Dawes rolls then or Indian Censuses by the mid-1900s?

Do you have records from Christian missionaries about your ancestors' whereabouts then?

Beyond than a family tree or enrollment certificate, what "evidence" do you currently possess to prove that you are properly enrolled by tribe?

Otherwise, how do you really know that you belong?

These are the inherently biased questions today's disenrollees are facing, in defense of their very existence.

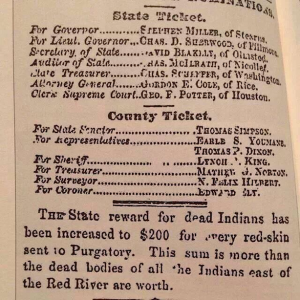

That despite the fact that county vital records from the late 1800s are almost non-existent for Indian women; that federal Indian rolls are inherently incomplete (Angelique A. EagleWoman & Wambdi A. Wastewin, Tribal Values of Taxation Within the Tribalist Economic Theory, 18 Kan.J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, 1, 7 (2008)); that Christian missionary records are antithetical to tribal longevity; and above all, that we primarily know we are tribal as a matter kinship and oral teachings, not some colonialist document.

That despite the fact that county vital records from the late 1800s are almost non-existent for Indian women; that federal Indian rolls are inherently incomplete (Angelique A. EagleWoman & Wambdi A. Wastewin, Tribal Values of Taxation Within the Tribalist Economic Theory, 18 Kan.J.L. & Pub. Pol’y, 1, 7 (2008)); that Christian missionary records are antithetical to tribal longevity; and above all, that we primarily know we are tribal as a matter kinship and oral teachings, not some colonialist document.

Unless you stand prepared to immediately produce written evidence of your belonging, you could be next in line for the disenrollment guillotine. In fact, disenrollment is not about even the best evidence, let alone the truth, of one's ancestry or genealogy or a tribal peoples' anthropology.

Disenrollment is a means to a certain end---the termination of those who are subject to its "process."

For me, I know I belong in Covelo because my grandma told me I was Nomlaki and Concow, my family was able to complete a family tree for me going back to my great grandma, and my tribe affirms that my she was an original allottee of the Round Valley Reservation. But I do not have any colonialist record of my great grandma's birth in the late 1800s or of her original allotment of land in Covelo. I hope I am not next.

Today's tribal leaders--the most revered living members of our communities--should hope they are not next either. Consider this haunting "facebook" of former tribal leader-disenrollees.

Tribal leaders, including founding Indian fathers and mothers, are even being disenrolled, posthumously. Even the descendants of Indian Treaty signers are being disenrolled. So much for honoring our ancestors.

Indian leaders are always subject to ouster for making wrong or unpopular decisions. That's just tribal democracy, at least theoretically. But tragically, they are also increasingly subject to disenrollment when or if the tribal political tide turns against them.

Disenrolling immediate past-leaders has proven to be an effective way for new leaders to stave off any future election challenge from those past leaders, and to stay in power indefinitely.

On the flipside, disenrollment can come back to haunt those who disenroll. Dictators who disenroll their kin worry that what's good for the goose could, sooner or later, be good for the gander. At least that's what worried the Dry Creek Rancheria Tribal Council, who after terminating 75 of their relatives last year, passed a 10-year disenrollment moratorium to prevent their own disenrollment.

Those of our tribal leaders who make good-hearted decisions---disenrollment not being one of them---should not have to govern while worried about being disenrolled for making a wrong or unpopular choice. And nobody should have to live with even the most remote worry of being terminated by their own people.

My point: Every single one of us could be next. That is, unless or until we, standing on the shoulders of our tribal leader giants, find a cure to the disenrollment epidemic.

Gabriel “Gabe” Galanda is the Managing Partner at Galanda Broadman. He belongs to the Round Valley Indian Tribes. Gabe can be reached at 206.300.7801 or gabe@galandabroadman.com.

"We see ourselves as filling niches that big firms cannot fill. We increasingly represent tribal individuals . . .," Galanda said, adding that the firm can also often represent tribe members without running into the conflicts — with, say, a developer or energy company — that a larger law firm might hit upon. . . .