Here.

NFL Super Bowl Champion Michael Bennett Hosts Free Sports Camp for Tribal Boys & Girls at Tulalip Sunday

Super Bowl Champion Michael Bennett will continue his outreach to Indigenous youth with a sports camp at the Tulalip Tribes Sports Complex on Sunday, June 23, 2019.

For the third summer in a row, Michael will take time out of his busy life to show Indigenous children that they matter, and to encourage them to live a healthy and active lifestyle.

“I believe that Native kids matter,” said Michael. “We must amplify the voices of Native children because they are the original Americans.”

Indigenous youth are the most vulnerable youth group in the United States. Over 25% Indian children live in poverty and 30% are obese. Native youth graduate from high school at a rate 17% lower than the national average. Native youth suffer the highest juvenile suicide rate, at more than double rate for the Caucasian youth suicide. Native youth experience PTSD at a rate of22%—triple that of the general population.

"We all have a duty to join forces against the oppression of any people," Michael continued.

Doing and giving what he can to improve life for Indigenous youth, Michael and the Bennett Foundation conducted a sports camp on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation in South Dakota, in 2017. Last year, Michael hosted Lummi and Nooksack 306 youth at a closed Seattle Seahawks practice at the team’s headquarters, as well as Native girls from various Pacific Northwest tribal communities at his Girls Empowerment Summit event at Garfield High School in Seattle.

This Sunday at Tulalip, over 500 Indigenous boys and girls are expected to attend. Michael will run sports drills and exercise with the youth and impart to them the need to eat nutritious foods, make healthy lifestyle decisions, and respect one’s self—because each of their lives are valued.

Michael’s Foundation, headquartered in Hawaii, has partnered with the Tulalip Tribes, the Snohomish County-Tulalip Unit of the Boys & Girls Club, Jaci McCormack’s Rise Above non-profit, and Indigenous rights law firm Galanda Broadman, PLLC, to hold the sports camp.

The sports camp will run from 1 to 3 PM; registration begins at noon. Registration for youth, ages 7 to 18, is free and still open at this link.

Interior’s Indian Depopulation Idea

Late last year the U.S. Department of the Interior began to consider whether Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agencies should cease issuing Certificates of Indian Blood (CDIBs). Interior’s idea, if realized, would depopulate and weaken Indian Country.

Indian lawyer Bree Black Horse describes the “federal Indian”: an Indian who is no longer or has never been enrolled by a federally recognized tribe, yet who still qualifies as “Indian” under various federal laws. Any elimination of BIA CDIBs would threaten federal Indian relatives’ existence, as well as the cultural, legal, and financial strength of tribal governments and urban Indian organizations.

In September 2018, Interior’s BIA Director Daryl LaCounte in Washington, D.C., issued an inter-department memo to BIA Regional Directors throughout the country, explaining that his office was “considering whether to end the practice of [the] BIA specifically issuing CDIBs.” In turn, the Regional Directors issued “Dear Tribal Leader” letters to the tribes in their region, “surveying” tribal concerns about the proposal. In a November 20, 2018, email to me, Director LaCounte suggested that “[t]here is no proposal to cease issuing CDIB’s.” But the fact remains that the Trump Administration has floated idea of ending the BIA’s practice of CDIB issuance.

According to FOIA records I obtained from Interior, Tribes as well as Alaska Native Villages and Corporations unanimously responded to BIA Regional Directors expressing concern about or opposition to the Central Office’s idea.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, for instance, explained that CDIBs allow “non-enrolled Indians” to qualify for federal programs and services, including educational loans and farming and ranching assistance. Those federal Indians also qualify for health care through the Indian Health Service (IHS) and they are included in that agency’s self-governance funding calculations for tribal clinics and urban Indian health care organizations. Without CDIBs, those relatives could be excluded from IHS health care and the calculus that results in critical federal medical funding for tribal and Alaska Native governments and communities.

The Inter-Tribal Council of the Five Civilized Tribes pointedly asked the BIA Eastern Oklahoma Region: “How will the BIA continue to provide services to Indians who are not citizens of a Tribe?” The BIA responded: “A policy determination has not been made as to whether or not the BIA has an obligation to provide CDIB services to non-tribal Indians.” The BIA is wrong.

Interior’s course of conduct in issuing CDIBs to “non-tribal Indians,” for at least the last four decades according to Paul Spruhan, has established an enforceable policy determination—one that obligates the BIA to provide CDIB and related social services to those federal Indians, as well as tribal governments who afford those relatives services. Wilkinson v. Legal Servs. Corp., 27 F.Supp.2d 32, 60 (D.D.C. 1998).

Standing Rock further explained to the BIA how CDIBs are “critical to the exercise of federal criminal jurisdiction under the Major Crimes Act” over certain non-enrolled Indians, without which “the Department of Justice ability to prosecute crimes in Indian Country would be severely hampered.” In other words, fewer Indians would be considered “Indian” for purpose of federal criminal prosecution; as non-Indians, legally speaking, they could exacerbate the public safety crisis in Indian Country caused by Oliphant. The Tribe decried any change in BIA policy as an “abdication of the responsibility to issue CDIBs” as part of the United States’ various trust responsibilities to tribes and Indians.

The most common criticism of Interior’s CDIB survey was that it lacked any prior tribal consultation. The Asa’carsamiut Tribal Council of Alaska, for example, expressed that it “feels strongly conducting a Tribal Consultation, instead of a survey, is the appropriate way for the BIA to address this issue.” The Muskogee (Creek) Nation flat refused to answer the BIA’s survey, instead demanding “proper and appropriate Tribal Consultation.”

In response to a question from the Five Civilized Tribes about whether the BIA would consult with Tribes, the BIA demurred, explaining that its “Central Office has not made a final determination as to whether or not consultation is necessary.” Consultation would in fact be necessary as a matter of Interior’s own consultation policy, or tribes could also sue Interior and BIA officials under the federal Administrative Procedures Act (APA) to enjoin and set aside any policy change.

Tribes and Alaska Native Villages and Corporations brought moral issues of indigenous belonging to Interior’s attention, too. The Association of Village Council Presidents of Alaska cited the need for “preservation of our tribal members” and otherwise observed that the BIA’s “CDIB card program is an important way to provide evidence of Alaska Native/American Indian descent.”

Even BIA Pacific Regional Director Amy Dutschke agreed: “the BIA should continue to issue CDIBs,” explaining that they are “beneficial to many individual California Indians, whether they are members of a Federally Recognized Tribe or not.” Alluding to the need for Indian inclusion in the Golden State—where generations of Indians have been killed, exiled, terminated, and disenrolled— Director Dutschke urged “the widest positive impact on the Indian people of California” through CDIBs.

In all, Interior’s proposal or idea to end BIA CDIB issuance would depopulate Indian Country and erode our collective strength in numbers. Tribes and Alaska Native Villages and Corporations would be weakened in the process.

To be clear: blood quantum is systematically destroying us. It is a European racial fiction and colonial device that the United States introduced to us—and we in turn blindly adopted as our own norm—since the federal allotment and assimilation era over a century ago. Blood quantum will lead to our eradication, if not at our own doing, by federal politicians or judges who see tribes as unconstitutional racial groups. See Brackeen v. Zinke, 338 F. Supp. 3d 514 (N.D. Tex. 2018).

We must unravel the various fibers of blood quantum, including CDIBs, which are now deeply woven into the fabric of tribal sovereignty and belonging, and the federal Indian trust responsibility owed to all Indians—whether enrolled, non-enrolled, reservation, or urban. That will take time, if not generations. But that unraveling should not occur through an idea stitched by the Trump Administration to a boilerplate “Dear Tribal Leader” letter and survey. Instead, that unraveling must start with us, especially the Tribes and Indians who wear that fabric today.

Gabriel “Gabe” Galanda is the managing lawyer at Galanda Broadman. He belongs to the Round Valley Indian Tribes. Gabe can be reached at 206.300.7801 or gabe@galandabroadman.com.

Gabe Galanda Named Among ‘Native Business Top 50 Entrepreneurs’

Native Business Magazine has named Gabe Galanda among “Native Business Top 50 Entrepreneurs,” a cohort of “Native business founders and leaders who are demonstrating ingenuity, professionalism and self-determination.”

In the Accounting & Legal sector, the magazine underlined “the positive influence on Indian Country of…Gabriel Galanda, a member of the Round Valley Indian Tribes of California, who started the law firm Galanda Broadman, PLLC.”

Gabriel “Gabe” Galanda is the managing lawyer at Galanda Broadman. He belongs to the Round Valley Indian Tribes. Gabe can be reached at 206.300.7801 or gabe@galandabroadman.com.

Galanda Broadman and Gabe Galanda Ranked Among Nation's Best in Native American Law

Galanda Broadman has been named one of the nation's premier law firms in Native American Law for 2019 by Chambers USA: America's Leading Lawyers for Business.

Gabe Galanda has also been named among he best lawyers in Native American Law nationally.

Chambers USA rankings are compiled from confidential, in-depth interviews with clients and attorneys from across the country. The assessments are based on technical legal ability, client service, diligence and other qualities most valued by clients.

Galanda Broadman, PLLC, is an American Indian-owned law firm with offices in Seattle and Yakima, Washington and Bend, Oregon. The firm is dedicated to advancing tribal Treaty and other sovereign legal rights, and Native American civil rights.

Washington State Corrections Religious Laws: "Changing the Language, Changing the Culture"

“Language is culture and culture is behavior. If you change the language you change the behavior.”

These are teachings from late Blackfeet language preservation advocate Darrell Kipp, which Blackfeet Seattle City Councilwoman Debora Juarez now passes on.

The State of Washington just made a change to its language—regarding a single word in state statute—that will reform institutional culture and behavior throughout our state corrections system.

On April 23, 2019, Governor Jay Inslee signed HB 1485—a bill sponsored by Alaska Native Representative Debra Lekanoff—into Washington State law. The bill amends a handful of statutes by replacing the Christian word “chaplain” with “religious coordinator,” as applicable to the state’s Departments of Corrections (DOC); Social and Health Services (DSHS); and Children, Youth and Family Services (DCYFS).

Gabe Galanda and Washington State Representative Debra Lekanoff (Tlingit/Aleut), HB 1485’s prime sponsor

Oxford defines “chaplain” as “a priest or other Christian minister who is responsible for the religious needs of people in a prison, hospital, or in the armed forces.” But for inmates of Jewish, or Hindu, or Buddhist, or Muslim, or Indigenous faith, chaplaincy is not a religious norm that fits neatly or at all with their faith practices.

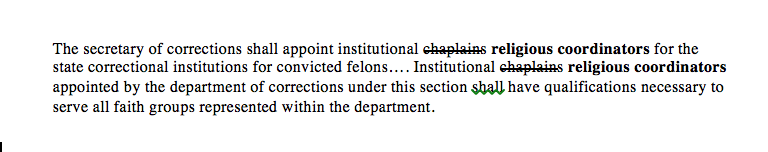

“Religious coordinator,” on the other hand, is a term that accommodates all faith groups, as illustrated by the now amended RCW 72.01.210:

Although this language change might be cynically viewed as simply more political correctness, it is not—it is reformational.

The language change will help diversify state agencies like the DOC, which, as of early 2019, employed 14 chaplains statewide—none were ethnic minority and only one was female. As a Jewish faith leader testified before the State Legislature, members of the Jewish faith do not honor chaplaincy as a faith institution, and could not bring themselves to even apply for a state chaplain position.

Non-Western faith practitioners might now think of becoming a state religious coordinator and helping our incarcerated state and tribal citizens seek and obtain spiritual rehabilitation.

More importantly, the language will, in practice, put non-Western faith practices—like Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Indigenous spirituality—on an equal footing with Christianity.

Until now there have been too any occasions when traditional Indigenous spiritual ways have been subjugated to Christian faith practices; when our ways have been consciously or subconsciously viewed and treated by state officers as different, foreign, or even worse.

Recall, for example, in 2010, when a Christian DOC “religious programs manager outlawed tribal sacred medicines, including tobacco, sage, sweetgrass and lavender…barred fry bread and salmon, preventing the prisoners from traditionally breaking four-day fasts during Change of Seasons rituals…scaled back Sunday sweat-lodge ceremonies [and] altered what an inmate could store in his sacred items shoebox, causing feather fans and beadwork to be disrespected by corrections officers” (Seattle Times).

By deemphasizing Christianity in three state agencies—including DSHS and DCYFS, which supervise our youth in custody—all other faith practices will elevate to equal status. This shift will empower inmates of non-Western faith; they will no longer feel spiritually “lesser than.”

In particular, Indigenous inmates will be more empowered to seek out opportunities to smudge, sweat, sing, drum, and participate in other spiritually rehabilitative traditional practices.

More broadly, by doing away with the word “chaplain,” Indigenous peoples both in and out of state Iron Houses will help reverse the effects of what Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s calls “spiritual subjugation,” which has occurred in great part through “the conscious elevation of the language of the coloniser.” (Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature (1986)).

Although the term “religious coordinator” does not derive from our language either, we can and will consciously elevate Indigenous spiritual ways by affixing our own cultural power to the new term.

Gabriel “Gabe” Galanda is the managing lawyer at Galanda Broadman. He belongs to the Round Valley Indian Tribes. Gabe can be reached at 206.300.7801 or gabe@galandabroadman.com.

Bree Black Horse: Washington State Legislature Honors Decedents and Survivors

The Washington Legislature has passed and Governor Inslee is expected to sign Senate Bill 5163, which significantly amends Washington’s wrongful death and survival statutes to allow parents, siblings and non-resident parents to bring suits based on the death of adult children that were previously barred. The amendments also expand recoverable damages.

History of Washington’s Wrongful Death And Survival Statutes

Beginning in the early twentieth century, the Washington State Legislate enacted a series of statutes that gave particular family members the ability to sue for the wrongful death of a loved one. But these statutes specifically excluded certain groups of beneficiaries from bringing suit to recover for the death of a loved one. For example, the parents of an adult child who was unmarried and had no children could not sue for the wrongful death of that loved one unless they were financially dependent on that adult child. Further, even if the parents were financially dependent on the adult child, they could not bring suit if they were not United States residents.

The Legislature made the 2019 amendments in part as a result of the fallout from the tragic 2015 Ride the Ducks crash in Seattle, Washington. There, several young people from other counties died in that crash, but their loved ones were denied standing to bring an action to recover for the loss of their loved ones because the family members were not United States residents at the time and their families did not financially depend on their deceased adult children. This bill similarly addresses this issue as applied to immigrant workers and their families, removing limitations previously championed by companies reluctant to pay damages arising from workplace injuries. The bill also impacts the ability of families to recover on behalf of disabled adult family members who generally lack financial dependents.

The amendments resolve issues stemming from outdated and racist laws that viewed farmhand children as chattel valued only as an economic contributors, and passed with the intent to prohibit Chinese nationals working on railroads and in mines during the early twentieth century from recovering on behalf of deceased family members.

Experts in the legal field have explained that Washington’s former wrongful death laws make it “cheaper for a defendant to kill a plaintiff than to injure him [or her].” This is particularly true for single adults without children who do not financially support their children or siblings.

Healthcare providers, local governments and state Republicans strongly opposed the amendments.

Amendments To Washington’s Wrongful Death And Survival Statutes

Washington’s wrongful death and survival statues include RCW 4.20.010, 4.20.020, 4.20.046, 4.20.060, and 4.24.010.

For instance, under the general wrongful death statute, the personal representative of a loved one’s estate can bring a cause of action on behalf of specified beneficiaries for damages they suffered as a result of the decedent’s death such as monetary losses and damages resulting from the loss of the relationship with the loved one. RCW

There are two tiers of beneficiaries in a general wrongful death action. The primary beneficiaries are the loved one’s spouse or domestic partner, and children. The secondary beneficiaries are the parents and siblings, but under the previous statute, they could only recover if there are no other primary beneficiaries, they were dependent on the decedent for support, and they resided within the United States at the time of the decedent’s death.

Under a general survival action, any cause of action the loved one could have brought prior to death may be brought by the personal representative of the decedent’s estate. The recoverable damages include pecuniary losses to the state such as loss of earnings, medical expenses, and funeral expenses. The estate also may recover, on behalf of beneficiaries in the general wrongful death statute, damages for the pain and suffering, anxiety, and emotional distress suffered by the decedent.

The 2019 legislation amended the general wrongful death and survival statues to change the beneficiaries entitled to recover as well as the damages available under these actions.

With regard to beneficiaries, the bill removed the dependency and residency requirements for secondary beneficiaries—parents and siblings—under the wrongful death statute, RCW 4. Now, a parent or sibling may be a beneficiary of the action if there is no spouse, domestic partner, or child, without having to show dependence on the deceased loved one and regardless of whether the parent or sibling resided in the United States at the time of the loved one’s death.

On damages, the bill specified that both economic and non-economic damages are recoverable against the person or entity causing the death under the general wrongful death statute in such amounts the jury determines to be just under the circumstances of the case.

The bill also removed the dependency and residency requirements for secondary beneficiaries—siblings and parents.

The legislature estimated that the bill would result in a twenty percent increase in claims, which would be about fifteen to eighteen cases per year.

The bill now awaits Governor Jay Inslee’s signature.

Bree is an associate in the Seattle office of Galanda Broadman and an enrolled member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. Her practice focuses on defending individuals’ civil rights in federal, state and tribal courts. She can be reached at (206) 735-0448 or bree@galandabroadman.com.

Indian Treaty Rights Weigh in the Supreme Court’s Balance of Herrera v. Wyoming

By Joe Sexton

In January, the United States Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Herrera v. Wyoming, a Treaty hunting rights case. Although some commentators suggest the case will lead to a narrow decision with little shift in Indian Law jurisprudence, and the High Court’s recent decision in Cougar Den certainly supports such optimism, Herrera may ripple deep into Indian Country and affect tribal Treaty rights nationwide.

The facts of the case are generally undisputed. In January 2014, Clayvin Herrera along with other Crow tribal members stalked elk on the Crow Reservation in Montana near Eskimo Creek. Herrera and his fellow hunters followed the elk off the Crow Reservation into the Big Horn National Forest in the State of Wyoming. The hunters killed three elk in the national forest and brought the meat back to the Crow Reservation in Montana to feed themselves and members of their tribe over the winter. Herrera asserted a Treaty right to hunt on “unoccupied lands of the United States” within territory the Crow Tribe had ceded to the United States under the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868; at the time of that particular Treaty, the lands where Herrera killed the elk were part of the Crow Tribe’s unoccupied ceded territory. Wyoming charged and tried Herrera for two misdemeanors despite his Treaty-reserved right: taking an antlered big game animal without a license and being an accessory to such a taking.

The Wyoming trial court denied Herrera’s motion to dismiss and granted the state’s motion to exclude any mention of Herrera’s Treaty rights at his criminal trial. Barred from even mentioning his Treaty right, Herrera was convicted of both counts. A Wyoming appellate court affirmed the trial court’s decisions and the Wyoming Supreme Court denied review. Ultimately, the Wyoming appellate court held that Mr. Herrera’s Treaty claims were not only barred under the theory that Wyoming’s admission to the Union abrogated the Crow Tribe’s Treaty rights as the 10th Circuit held in Repsis, but that Herrera’s claims were also barred by the legal doctrines of res judicata and collateral estoppel.

Herrera appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, presenting the question “[w]hether Wyoming’s admission to the Union or the establishment of the Bighorn National Forest abrogated the Crow Tribe of Indians’ 1868 federal Treaty right to hunt on the “unoccupied lands of the United States.”

Wyoming relies on Crow Tribe of Indians v. Repsis, 73 F.3d 982 (10th Cir. 1995) for its principal argument—that the Crow Tribe’s Treaty right to hunt off reservation, at least on unoccupied lands of the United States within Wyoming, was “repealed by the act admitting Wyoming into the Union.” Id. at 994. The Tenth Circuit in Repsis, had, in turn, rested its decision on the U.S. Supreme Court’s holding a century earlier in Ward v. Race Horse, 163 U.S. 504 (1896). In this 19th Century decision, the Supreme Court held that legislation admitting Wyoming into the union as a state abrogated tribal Treaty rights to hunt on United States land because honoring those Treaty rights would mean Wyoming was “admitted into the Union not as an equal member, but as one shorn of a legislative power vested in all the other states of the Union.” Id. at 514. This was known as the “equal footing doctrine,” and is contrary to the general accepted doctrine arising in the 20th Century that states must honor tribal Treaty rights under the United States Constitution’s Supremacy Clause unless Congress has expressly abrogated those rights. See Antoine v. Washington, 420 U.S. 194, 201-02 (1975).

Mr. Herrera countered that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Race Horse in 1999. See Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, 526 U.S. 172 (1999). Consequently, he argues the portion of Repsis that relies on Race Horse to extinguish the Crow Tribe’s Treaty right to hunt off reservation is no longer good law. In the absence of Race Horse, Mr. Herrera’s Treaty rights remain viable and state courts and governments are bound to honor them.

During oral argument, questioning from Justice Sotomayor to the attorney for Wyoming focuses on the danger to all tribal Treaty rights if the Supreme Court issues a broad decision in Herrera in favor of Wyoming. Justice Sotomayor wanted to know what language in the Treaty at issue in Herrera could result in cancelation of Crow members’ hunting rights throughout the state of Wyoming. Put another way, Justice Sotomayor is drilling down on the fact that neither the terms of the Treaty, nor a subsequent Congressional act expressly limiting or changing those terms provides that the Treaty rights were “intended to expire upon [Wyoming’s] statehood” as Wyoming’s attorney argued:

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: So tell me what in the treaty says [the treaty right to hunt off reservation] automatically terminates. I saw a lot of conditions. I saw the game disappearing, the land becoming occupied, but I don’t see on statehood or even anything approaching it.

MR. KNEPPER: The – the –

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Where – where in – just point to something in the treaty language

MR. KNEPPER: Sure . . . Your Honor, the – the decision rests on the conclusion that unoccupied lands must be of the character of the lands denominated as hunting districts, and that hunting districts were a specific kind of land understood, and that upon settlement, and, you know, there’s a – there’s a process, but culminating in statehood. . . .

I think that if what you’re asking is are there unoccupied lands within the meaning of the treaty anymore within the State of Wyoming, that’s – that’s what the decision both in Race Horse and in – and in Repsis concluded, that those – those lands – those lands have disappeared. They no longer exist within the State of Wyoming.

Simply, according to Wyoming the Crow Tribe’s Treaty rights “disappeared” upon Wyoming’s admission to the union, regardless of the absence of any Treaty language indicating its rights were subject to the admission of states into the Union and in the absence of any express intent on the part of Congress in admitting Wyoming to extinguish all tribal Treaty rights within the state. But Wyoming’s reliance on Race Horse to suggest that Treaty rights can be extinguished by implication imperils all tribal Treaty rights throughout Indian Country. This threat arises not only from the “equal footing doctrine” Wyoming argued, should be re-embraced in the 21st Century, but—in the event an expansive shift on the law of Treaty construction that may result from Herrera—any argument a state or the federal government might make that Treaty rights are extinguished by implication through some mechanism not expressly negotiated as a condition in the Treaty.

Commentators may be right regarding Herrera and its impending outcome—the holding could be narrow. In any event, this is a case to follow for anyone concerned with tribal Treaty rights and their future in turbulent 21st Century America.

Joe Sexton is a partner with Galanda Broadman, PLLC. Joe’s practice focuses on tribal sovereignty issues, including complex land and environmental issues, and economic development matters. He can be reached at (509) 910-8842 and joe@galandbroadman.com.

DOJ Approves Chehalis Tribe’s Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction Process

Left to Right: Janet Stegall, Grant Writer; Jerrie Simmons, Court Director, Jessie Goddard, Vice Chairwoman; Misty Secena, General Manager.

Oakville, Wash. – The Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation (Chehalis Tribe) is the 24th Federally Recognized Indian Tribe in the United States to fully implement and enact the Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction under the Indian Provisions of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) to have special jurisdiction over non-Native offenders. The tribal government took many steps leading up to the final approval on March 20, 2019 by the Department of Justice.

Numerous Chehalis Tribal member women served as the driving force behind the process of grant writing, staffing the Tribal Court and revising the Chehalis Tribal Code. Janet Stegall, responsible for writing the VAWA grant, stated as a Chehalis Tribal woman, “I am overwhelmed with the relief that an unforgivable injustice is going to be able to be brought to justice in the future.” Misty Secena, General Manager, hit the ground running by initiating meetings towards implementing the VAWA grant.

Jerrie Simmons, Chehalis Tribal member and the Tribal Court Director with many years’ experience as an Indian Law Lawyer, stated this is the first step in regaining the ability to prosecute non-Natives in Tribal court since the Oliphant v. Suquamish Tribe case of 1978. This case went to Supreme Court with a 6-2 majority vote in favor of Oliphant setting the precedent that non-Natives could not be prosecuted for crimes on tribal territory. This law stood with no latitude for over thirty years until the 2013 VAWA pilot project when the Umatilla (Org.), Pascua Yaqui (Ari.), and Tulalip Tribes (Wash.) became the first three tribes to exercise special criminal jurisdiction on domestic and dating violence.

The tribes that implement this program must meet all of the civil right protections that the US constitution guarantees to a criminal defendant. Therefore, part of the pre-approval process involved revising the Chehalis Tribal Domestic Violence and Criminal Codes to comply with the Federal Law.

The Chehalis Tribe, along with others across the nation, are awaiting expansion of the law to enable prosecution for crimes related to domestic violence; such as crimes against children, crimes against a public officer, etc. Implementation of the VAWA criminal jurisdiction and others will help protect the tribal reservations for current and future generations.

Gabe Galanda: "Reviving Tribal Kinship"

On Thursday, Gabe Galanda delivered a talk, “Reviving Tribal Kinship,” as part of the Indigenous Peoples Law & Policy Program’s Distinguished Alumni Speaker Series at the University of Arizona College of Law.

Gabe’s talk in Tucson was an expanded version of a 10-minute Insight Blast, “Reimagining Tribal Citizenship,” which he delivered at Harvard University’s Kennedy School last spring.

Gabe calls upon tribal communities to reconcile traditional tribal kinship systems and rules with modern Native nationhood, in order to countervail the destruction caused to Indian peoples by colonialism and federalism, particularly through non-indigenous practices like blood quantum and disenrollment.

The slides from his latest talk can be viewed here.

Gabriel “Gabe” Galanda is the managing lawyer at Galanda Broadman. He belongs to the Round Valley Indian Tribes. Gabe can be reached at 206.300.7801 or gabe@galandabroadman.com.