The Washington State Supreme Court held 5-4 today that AUTO’s lawsuit attacking Tribe-State Fuel Tax Agreements can move forward. The majority found that Tribes are not indispensable parties to the lawsuit. Plainly, this means that the suit can proceed and that for now the Washington Automotive United Trades Organization (AUTO) can continue to attack Tribal governments through a lawsuit against the state.

At the core of its lawsuit, AUTO argues that the state, Governor Christine Gregoire, and the state Department of Licensing are violating the Washington Constitution by entering into the fuel compacts with Tribes and that the legislative system surrounding the compacts itself is illegal.

The decision, AUTO I, was decided on procedural grounds. But like most procedural decisions employing balancing tests, judges can rationalize reversal or affirmation. As the majority itself pointed out: “As with all equitable standards, the proper application of CR 19(b) involves a careful exercise of discretion and defies mechanical application.” Which means that judges can justify whatever result they desire.

But the anti-tribal/state majority did make some helpful intermediate findings: First, the tribes are necessary parties. As a matter of civil procedure, parties are necessary when they claim a protected interest in a lawsuit. The majority held that the tribes’ interests in the fuel tax regime are both profound and not adequately represented by the state. If AUTO wins, tribes lose big.

Second, the majority soundly endorsed the continuing sovereign immunity of tribes. Justice Stephens offered the following nuanced discussion, without citation, of tribes’ ability to manage their own immunity from suit:

In fact, an Indian tribe may cabin the extent of its waiver. The greater power to remain utterly immune from suit encompasses the lesser power to consent to suit only on a particular claim or in a particular forum or by a particular party. Sovereign immunity is not an all or nothing proposition, and a narrow waiver does not destroy immunity for all purposes.

So far so good. But on indispensability itself, the Court showed its colors, achieving the result it wanted at the cost of bad legal analysis. Indispensability (after necessity and inability to join have been decided) asks whether the case can proceed “in equity and good conscience” without the absent party in light of four factors.

Analyzing the first factor, prejudice to the tribes, the Court held that the tribes would be severely prejudiced. As the majority noted, “[t]his first factor strongly favors dismissal.” Usually, with immune parties, this is the end of the discussion. This has certainly been the historic approach of Washington Courts.

The second factor is whether the Court can fashion relief to reduce such prejudice. The Court recognized that because AUTO’s solution – suing tribal officials who signed the fuel tax agreements – was as bad as the prejudice, “the second CR 19(b) factor favors dismissal.” The Court did not even really apply the third factor (adequacy of judgment without the tribes) but found that it counseled for dismissal anyway. If you’re keeping score, that’s three factors for dismissal, and zero factors against it.

Relying then completely on the fourth factor, the absence of remedy upon dismissal, the Court held that because “there appears to be no other judicial forum in which plaintiffs can seek relief, the plaintiff lacks an adequate remedy in the event of dismissal,” the case could not be dismissed.

In the end, even though the Court has dismissed similar suits over somewhat similar agreements on indispensability grounds, the state, and indirectly, the tribes, were before the wrong justices. The Court naively noted that, “Sovereign immunity is meant to be raised as a shield by the tribe, not wielded as a sword by the State.” But as is clear in this case, if courts force cases forward with indispensible parties, it’s a shield that immune parties can’t even employ without waiving.

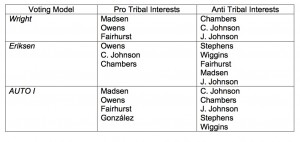

Here is the updated rough chart of Washington State Supreme Court voting tendencies:

In Wright and AUTO, which are the most analogous cases, only justices Madsen, Owens, and Fairhurst have come down on Tribal side of cases (justices González and Stephens were not on the Court for Wright.) The other end of the Court has congealed around both justices Johnson and Justice Chambers, and promises to be consistently resistant to protecting tribal interests.

We’re calling it AUTO Part One because Part Two will come, whether through review to the U.S. Supreme Court or through further litigation in the Washington State Courts. Either way, AUTO promises to carry even more profound risks to the Tribal-State fuel tax regime, and indirectly to the sovereignty of Washington tribes themselves.

Anthony Broadman is a partner at Galanda Broadman PLLC. He can be reached at 206.321.2672, anthony@galandabroadman.com, or via www.galandabroadman.com.