By Anthony Broadman

Tribal judicial independence is good governance. But even more importantly, an independent Indian judiciary is a human right for those within a Tribal Court’s jurisdiction.

A strong independent judiciary provides Tribes with a mechanism to resolve disputes that would otherwise undermine political stability. It also provides Tribal members and non-Indians with forums to resolve disputes that would otherwise be brought in non-Tribal forums and further diminish Tribal sovereignty and authority.

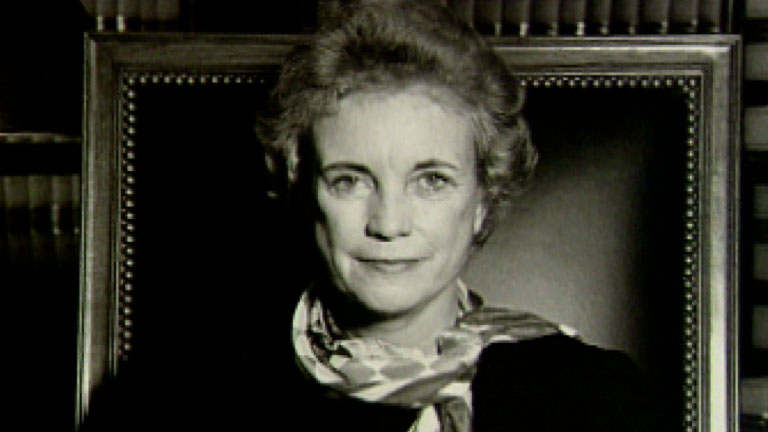

The notion that as a practical policy matter, Tribes need independent judiciaries is part of Tribal judicial consciousness. As then Justice Sandra Day O’Connor observed in 1997:

One of the most important initiatives is the move to ensure judicial independence for tribal judges. Tribal courts are often subject to the complete control of the tribal councils, whose powers often include the ability to select and remove judges. Therefore, the courts may be perceived as a subordinate arm of the councils rather than as a separate and equal branch of government. The existence of such control is not conducive to neutral adjudication on the merits and can threaten the integrity of the tribal judiciary.

Sandra D. O'Connor, Lessons from the Third Sovereign: Indian Tribal Courts, 33 Tulsa L. J. 1, 5 (1997).

This observation is no longer surprising to Tribal Governments, Tribal Judges, or lawyers practicing in Tribal jurisdictions. And it’s a function of what Justice O’Connor called “our own political culture” which “teaches us that we must be ever vigilant against those who would strong-arm the judiciary into adopting their preferred policies.” Sandra Day O’Connor, Remarks on Judicial Independence, 58 FLA. L. REV. 1, 6 (2005).

For lawyers and judges who practice in both Tribal and non-Tribal forums, our legal-political culture imposes this value on Tribal courts. We cannot see anything other than the necessity of an independent Indian judiciary.

But rather than examining judicial independence as a practical benefit for Indian Country, as Justice O’Connor has done so successfully, Tribal judges and attorneys may also view the independence of an Indian judiciary as a critical human right for the Tribe and Tribal-members it serves.

Indeed, an independent judiciary is among the most basic human rights recognized under international law.

To comply with the United Nations principles of judicial independence, and be among the world’s true sovereigns, all nations must guarantee the independence of the judiciary, and “enshrine” it in their constitutions or laws. There “shall not be any inappropriate or unwarranted interference with the judicial process [and disciplinary and removal] proceedings should be subject to an independent review.”

Notably, Tribes who fail to comply with these tenets, violate their members’ human rights.

And as a matter of sovereignty, Tribes cannot have it both ways. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) protects the rights of Tribal nations and people but also imposes an obligation on Tribal governments, as the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People observed in 2008:

[The] wide affirmation of the rights of indigenous peoples in the Declaration does not only create positive obligations for States, but also bestows important responsibilities upon the rights-holders themselves. This interaction between the affirmation of rights and the assumption of responsibilities is particularly crucial in areas in which the Declaration affirms for indigenous peoples a large degree of autonomy in managing their internal and local affairs. Positive action by indigenous peoples themselves is by definition required for the exercise of their rights to maintain and develop institutions and mechanisms of self-governance. . . . In exercising their rights and responsibilities under the [UNDRIP], indigenous peoples themselves should be guided by the normative tenets of the Declaration. . . . The implementation of the Declaration by indigenous peoples may . . . require them to develop or revise their own institutions, traditions or customs through their own decision-making procedures. The Declaration recalls that the functioning of indigenous institutions should be “in accordance with international human rights standards” and calls for particular attention “to the rights and special needs of indigenous elders, women, youth, children and persons with disabilities,” including in the elimination of all forms of discrimination . . . . With an appropriate understanding of these provisions, the [UNDRIP] is a powerful tool in the hands of indigenous peoples to mainstream human rights within their respective societies in ways that are respectful to their cultures and values.

Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People, Rep. on Promotion and Protection of All Human Rights, Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Including the Right to Development, HRC, P75, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/9/9 (Aug. 5, 2008) (citation omitted).

As Justice O’Connor noted:

It takes a lot of degeneration before a country gets to be [2005] Zimbabwe. But if I might coin a phrase, we should avoid these ends by avoiding these beginnings.

58 FLA. L. REV. at 6.

We attorneys and judges, as officers of Tribal courts can and must avoid these ends—dictatorships—by avoiding these beginnings. And Tribal governments can and must avoid these ends by advancing the basic human rights of those they represent—as international human rights law requires.

Anthony Broadman is a partner at Galanda Broadman PLLC and serves as a Tribal Appellate Court Judge. He can be reached at 206.321.2672, anthony@galandabroadman.com, or via www.galandabroadman.com.